Alagappa University UG Part II English Semester IV Syllabus

Syllabus

Unit – I Lalajee - Jim Corbelt

Unit – II A Day‘s Wait - Hemmingway

Unit – III Two old Men - Leo Tolstoy

Unit –IV Little Girls wiser than - Men Tolstoy

Unit – V Boy who wanted more Cheese - William Elliot Griffir

Drama

Unit – VI Pygmalion - G.B. Shaw

Fiction

Unit – VII Swami and Friends - R.K. Narayanan

Tales from Shakespeare

Unit – VIII - The Merchant of Venice

Unit – IX - Romeo and Juliet

Unit – X - The Winter‘s Tale

Biographies

Unit – XI - Martin-Luther king - R.N. Roy

Unit – XII - Nehru - A.J. Toynbee

Grammar

Unit – XIII - Concord- Phrases and Clauses-Question Tag

Composition

Unit – XIV - Expansion of Proverbs

- Group Discussion

-Conversation (Apologizing, Requesting, Thanking )

References:

1. Sizzlers, by the Board of Editors, Publishers-: Manimekala Publishing House, Madurai.

2. Pygmalion – G.B. Shaw.

3. Swami and Friends – R.K. Narayan.

4. Tales from Shakespeare Ed. by the Board of Editors, Harrows Publications, Chennai.

5. Modern English – A Book of Grammar Usage and Composition by

N.Krishnaswamy, Macmillan Publishers.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

in what follows you will see material related to different units :

UNIT V

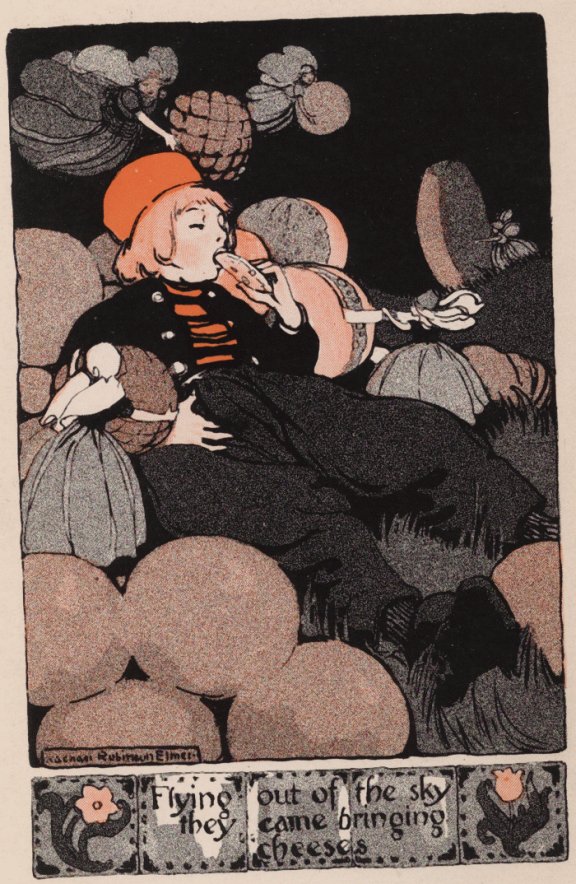

The Boy Who Wanted More Cheese

A Dutch Fairy Tale

Klaas Van Bommel was a Dutch boy, twelve years old, who lived where cows were plentiful. He was over five feet high, weighed a hundred pounds, and had rosy cheeks. His appetite was always good and his mother declared his stomach had no bottom. His hair was of a color half-way between a carrot and a sweet potato. It was as thick as reeds in a swamp and was cut level, from under one ear to another.

Klaas stood in a pair of timber shoes, that made an awful rattle when he ran fast to catch a rabbit, or scuffed slowly along to school over the brick road of his village. In summer Klaas was dressed in a rough, blue linen blouse. In winter he wore woollen breeches as wide as coffee bags. They were called bell trousers, and in shape were like a couple of cow-bells turned upwards. These were buttoned on to a thick warm jacket. Until he was five years old, Klaas was dressed like his sisters. Then, on his birthday, he had boy's clothes, with two pockets in them, of which he was proud enough.

Klaas was a farmer's boy. He had rye bread and fresh milk for breakfast. At dinner time, beside cheese and bread, he was given a plate heaped with boiled potatoes. Into these he first plunged a fork and then dipped each round, white ball into a bowl of hot melted butter. Very quickly then did potato and butter disappear "down the red lane." At supper, he had bread and skim milk, left after the cream had been taken off, with a saucer, to make butter. Twice a week the children enjoyed a bowl of bonnyclabber or curds, with a little brown sugar sprinkled on the top. But at every meal there was cheese, usually in thin slices, which the boy thought not thick enough. When Klaas went to bed he usually fell asleep as soon as his shock of yellow hair touched the pillow. In summer time he slept till the birds began to sing, at dawn. In winter, when the bed felt warm and Jack Frost was lively, he often heard the cows talking, in their way, before he jumped out of his bag of straw, which served for a mattress. The Van Bommels were not rich, but everything was shining clean.

There was always plenty to eat at the Van Bommels' house. Stacks of rye bread, a yard long and thicker than a man's arm, stood on end in the corner of the cool, stone-lined basement. The loaves of dough were put in the oven once a week. Baking time was a great event at the Van Bommels' and no men-folks were allowed in the kitchen on that day, unless they were called in to help. As for the milk-pails and pans, filled or emptied, scrubbed or set in the sun every day to dry, and the cheeses, piled up in the pantry, they seemed sometimes enough to feed a small army.

But Klaas always wanted more cheese. In other ways, he was a good boy, obedient at home, always ready to work on the cow-farm, and diligent in school. But at the table he never had enough. Sometimes his father laughed and asked him if he had a well, or a cave, under his jacket.

Klaas had three younger sisters, Trintje, Anneke and Saartje; which is Dutch for Kate, Annie and Sallie. These, their fond mother, who loved them dearly, called her "orange blossoms"; but when at dinner, Klaas would keep on, dipping his potatoes into the hot butter, while others were all through, his mother would laugh and call him her Buttercup. But always Klaas wanted more cheese. When unusually greedy, she twitted him as a boy "worse than Butter-and-Eggs"; that is, as troublesome as the yellow and white plant, called toad-flax, is to the farmer--very pretty, but nothing but a weed.

One summer's evening, after a good scolding, which he deserved well, Klaas moped and, almost crying, went to bed in bad humor. He had teased each one of his sisters to give him her bit of cheese, and this, added to his own slice, made his stomach feel as heavy as lead.

Klaas's bed was up in the garret. When the house was first built, one of the red tiles of the roof had been taken out and another one, made of glass, was put in its place. In the morning, this gave the boy light to put on his clothes. At night, in fair weather, it supplied air to his room.

A gentle breeze was blowing from the pine woods on the sandy slope, not far away. So Klaas climbed up on the stool to sniff the sweet piny odors. He thought he saw lights dancing under the tree. One beam seemed to approach his roof hole, and coming nearer played round the chimney. Then it passed to and fro in front of him. It seemed to whisper in his ear, as it moved by. It looked very much as if a hundred fire-flies had united their cold light into one lamp. Then Klaas thought that the strange beams bore the shape of a lovely girl, but he only laughed at himself at the idea. Pretty soon, however, he thought the whisper became a voice. Again, he laughed so heartily, that he forgot his moping and the scolding his mother had given him. In fact, his eyes twinkled with delight, when the voice gave this invitation:

"There's plenty of cheese. Come with us."

To make sure of it, the sleepy boy now rubbed his eyes and cocked his ears. Again, the light-bearer spoke to him: "Come."

Could it be? He had heard old people tell of the ladies of the wood, that whispered and warned travellers. In fact, he himself had often seen the "fairies' ring" in the pine woods. To this, the flame-lady was inviting him.

Again and again the moving, cold light circled round the red tile roof, which the moon, then rising and peeping over the chimneys, seemed to turn into silver plates. As the disc rose higher in the sky, he could hardly see the moving light, that had looked like a lady; but the voice, no longer a whisper, as at first, was now even plainer:

"There's plenty of cheese. Come with us."

"I'll see what it is, anyhow," said Klaas, as he drew on his thick woolen stockings and prepared to go down-stairs and out, without waking a soul. At the door he stepped into his wooden shoes. Just then the cat purred and rubbed up against his shins. He jumped, for he was scared; but looking down, for a moment, he saw the two balls of yellow fire in her head and knew what they were. Then he sped to the pine woods and towards the fairy ring.

What an odd sight! At first Klaas thought it was a circle of big fire-flies. Then he saw clearly that there were dozens of pretty creatures, hardly as large as dolls, but as lively as crickets. They were as full of light, as if lamps had wings. Hand in hand, they flitted and danced around the ring of grass, as if this was fun.

Hardly had Klaas got over his first surprise, than of a sudden he felt himself surrounded by the fairies. Some of the strongest among them had left the main party in the circle and come to him. He felt himself pulled by their dainty fingers. One of them, the loveliest of all, whispered in his ear:

"Come, you must dance with us."

Then a dozen of the pretty creatures murmured in chorus:

"Plenty of cheese here. Plenty of cheese here. Come, come!"

Upon this, the heels of Klaas seemed as light as a feather. In a moment, with both hands clasped in those of the fairies, he was dancing in high glee. It was as much fun as if he were at the kermiss, with a row of boys and girls, hand in hand, swinging along the streets, as Dutch maids and youth do, during kermiss week.

Klaas had not time to look hard at the fairies, for he was too full of the fun. He danced and danced, all night and until the sky in the east began to turn, first gray and then rosy. Then he tumbled down, tired out, and fell asleep. His head lay on the inner curve of the fairy ring, with his feet in the centre.

Klaas felt very happy, for he had no sense of being tired, and he did not know he was asleep. He thought his fairy partners, who had danced with him, were now waiting on him to bring him cheeses. With a golden knife, they sliced them off and fed him out of their own hands. How good it tasted! He thought now he could, and would, eat all the cheese he had longed for all his life. There was no mother to scold him, or daddy to shake his finger at him. How delightful!

But by and by, he wanted to stop eating and rest a while. His jaws were tired. His stomach seemed to be loaded with cannon-balls. He gasped for breath.

But the fairies would not let him stop, for Dutch fairies never get tired. Flying out of the sky--from the north, south, east and west--they came, bringing cheeses. These they dropped down around him, until the piles of the round masses threatened first to enclose him as with a wall, and then to overtop him. There were the red balls from Edam, the pink and yellow spheres from Gouda, and the gray loaf-shaped ones from Leyden. Down through the vista of sand, in the pine woods, he looked, and oh, horrors! There were the tallest and strongest of the fairies rolling along the huge, round, flat cheeses from Friesland! Any one of these was as big as a cart wheel, and would feed a regiment. The fairies trundled the heavy discs along, as if they were playing with hoops. They shouted hilariously, as, with a pine stick, they beat them forward like boys at play. Farm cheese, factory cheese, Alkmaar cheese, and, to crown all, cheese from Limburg--which Klaas never could bear, because of its strong odor. Soon the cakes and balls were heaped so high around him that the boy, as he looked up, felt like a frog in a well. He groaned when he thought the high cheese walls were tottering to fall on him. Then he screamed, but the fairies thought he was making music. They, not being human, do not know how a boy feels.

At last, with a thick slice in one hand and a big hunk in the other, he could eat no more cheese; though the fairies, led by their queen, standing on one side, or hovering over his head, still urged him to take more.

At this moment, while afraid that he would burst, Klaas saw the pile of cheeses, as big as a house, topple over. The heavy mass fell inwards upon him. With a scream of terror, he thought himself crushed as flat as a Friesland cheese.

But he wasn't! Waking up and rubbing his eyes, he saw the red sun rising on the sand-dunes. Birds were singing and the cocks were crowing all around him, in chorus, as if saluting him. Just then also the village clock chimed out the hour. He felt his clothes. They were wet with dew. He sat up to look around. There were no fairies, but in his mouth was a bunch of grass which he had been chewing lustily.

Klaas never would tell the story of his night with the fairies, nor has he yet settled the question whether they left him because the cheese-house of his dream had fallen, or because daylight had come.

____________________________________________________________________________

13742 Unit IV Little Girls Wiser Than Men

Written: 1885

Source: Translated by the Maudes

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

It was an early Easter. Sledging was only just over; snow still lay in the yards; and water ran in streams down the village street.

Two little girls from different houses happened to meet in a lane between two homesteads, where the dirty water after running through the farm-yards had formed a large puddle. One girl was very small, the other a little bigger. Their mothers had dressed them both in new frocks. The little one wore a blue frock, the other a yellow print, and both had red kerchiefs on their heads. They had just come from church when they met, and first they showed each other their finery, and then they began to play. Soon the fancy took them to splash about in the water, and the smaller one was going to step into the puddle, shoes and all, when the elder checked her:

'Don't go in so, Malásha,' said she, 'your mother will scold you. I will take off my shoes and stockings, and you take off yours.'

They did so; and then, picking up their skirts, began walking towards each other through the puddle. The water came up to Malásha's ankles, and she said:

'It is deep, Akoúlya, I'm afraid!'

'Come on,' replied the other. 'Don't be frightened. It won't get any deeper.'

When they got near one another, Akoúlya said:

'Mind, Malásha, don't splash. Walk carefully!'

She had hardly said this, when Malásha plumped down her foot so that the water splashed right on to Akoúlya's frock. The frock was splashed, and so were Akoúlya's eyes and nose. When she saw the stains on her frock, she was angry and ran after Malásha to strike her. Malásha was frightened, and seeing that she had got herself into trouble, she scrambled out of the puddle, and prepared to run home. Just then Akoúlya's mother happened to be passing, and seeing that her daughter's skirt was splashed, and her sleeves dirty, she said:

'You naughty, dirty girl, what have you been doing?'

'Malásha did it on purpose,' replied the girl.

At this Akoúlya's mother seized Malásha, and struck her on the back of her neck. Malásha began to howl so that she could be heard all down the street. Her mother came out.

'What are you beating my girl for?' said she; and began scolding her neighbor. One word led to another and they had an angry quarrel. The men came out, and a crowd collected in the street, every one shouting and no one listening. They all went on quarreling, till one gave another a push, and the affair had very nearly come to blows, when Akoúlya's old grandmother, stepping in among them, tried to calm them.

'What are you thinking of, friends? Is it right to behave so? On a day like this, too! It is a time for rejoicing, and not for such folly as this.'

They would not listen to the old woman, and nearly knocked her off her feet. And she would not have been able to quiet the crowd, if it had not been for Akoúlya and Malásha themselves. While the women were abusing each other, Akoúlya had wiped the mud off her frock, and gone back to the puddle. She took a stone and began scraping away the earth in front of the puddle to make a channel through which the water could run out into the street. Presently Malásha joined her, and with a chip of wood helped her dig the channel. Just as the men were beginning to fight, the water from the little girls' channel ran streaming into the street towards the very place where the old woman was trying to pacify the men. The girls followed it; one running each side of the little stream.

'Catch it, Malásha! Catch it!' shouted Akoúlya; while Malásha could not speak for laughing.

Highly delighted, and watching the chip float along on their stream, the little girls ran straight into the group of men; and the old woman, seeing them, said to the men:

'Are you not ashamed of yourselves? To go fighting on account of these lassies, when they themselves have forgotten all about it, and are playing happily together. Dear little souls! They are wiser than you!'

The men looked at the little girls, and were ashamed, and, laughing at themselves, went back each to his own home.

'Except ye turn, and become as little children, ye shall in no wise enter into the kingdom of heaven.'

அது ஒரு ஆரம்பகால ஈஸ்டர். ஸ்லெட்ஜிங் அப்போதுதான் முடிந்தது; முற்றங்களில் இன்னும் பனி கிடந்தது; கிராமத் தெருக்களில் ஓடைகளில் தண்ணீர் ஓடியது.

வெவ்வேறு வீடுகளைச் சேர்ந்த இரண்டு சிறுமிகள் இரண்டு வீட்டுத் தோட்டங்களுக்கிடையேயுள்ள ஒரு சந்தில் சந்திக்க நேர்ந்தது. பண்ணை முற்றங்கள் வழியாக ஓடிய அழுக்கு நீர் ஒரு பெரிய குட்டையை உருவாக்கியிருந்தது. ஒரு பெண் மிகவும் சிறியவள், மற்றவள் கொஞ்சம் பெரியவள். அவர்களின் தாய்மார்கள் அவர்கள் இருவருக்கும் புதிய ஃப்ராக்களை அணிவித்திருந்தனர். சின்னவள் நீல நிற ஃப்ராக் அணிந்திருந்தாள். மற்றவள் மஞ்சள் நிற அச்சு அணிந்திருந்தாள் .இருவருடைய தலையிலும் சிவப்புக் கைக்குட்டைகள் இருந்தன. மாதா கோயிலிலிருந்து அப்போதுதான் அவர்கள் வந்திருந்தார்கள். முதலில் தங்களுடைய அலங்காரங்களை ஒருவருக்கொருவர் காட்டிக்கொண்டார்கள். பிறகு அவர்கள் விளையாட ஆரம்பித்தார்கள். கொஞ்ச நேரத்துல தண்ணியில துள்ளி குதிச்சு சின்ன பொண்ணு குட்டைல இறங்க ஆரம்பிச்சதும், பெரியவள் அவளை சோதிச்சாள்:

"அப்படிப் போகாதே, மாலாஷா, உன் அம்மா உன்னைத் திட்டுவாள். நான் என் காலணிகளையும் காலுறைகளையும் கழற்றிவிடுவேன், நீ உன்னுடையதைக் கழற்றிவிடு.'

அவர்கள் அவ்வாறே செய்தார்கள்; பிறகு பாவாடையை தூக்கிக் கொண்டு ஒருவரை ஒருவர் நோக்கி நடக்க ஆரம்பித்தார்கள் மலஷாவின் கணுக்கால் வரை தண்ணீர் வந்தது, அவள் சொன்னாள்:

"ரொம்ப ஆழமா இருக்கு அகோல்யா, எனக்கு பயமா இருக்கு!"

"வாருங்கள்" என்றாள் மற்றவள். 'பயப்படாதீங்க. இது இன்னும் ஆழமாக செல்லாது.

அவர்கள் ஒருவரையொருவர் நெருங்கியபோது, அகோல்யா சொன்னாள்:

மாலாஷா, தெறிக்காதே. கவனமாக நட!"

அவள் இதைச் சொல்லும் முன்னரே மலாஷா தன் காலைக் குனிந்து அகோலியாவின் ஃப்ராக் மீது தண்ணீர் தெறித்தது., அகோலியாவின் கண்களும் மூக்கும் தெறித்தன. தன் மேலங்கியில் இருந்த கறைகளைக் கண்டதும் கோபம் கொண்டு மாலாஷாவைத் துரத்தி ஓடி அவளை அடித்தாள். மலாஷா பயந்துபோனாள், தான் சிக்கலில் மாட்டிக் கொண்டதைக் கண்டு, அவள் குட்டையிலிருந்து வெளியேறி, வீட்டிற்கு ஓடத் தயாரானாள். அப்போதுதான் அகோலியாவின் தாய் அந்த வழியாகச் சென்றுகொண்டிருந்தார். தனது மகளின் பாவாடை தெறித்திருந்ததையும், அவளுடைய சட்டைக் கைகள் அழுக்காக இருந்ததையும் கண்டு அவர் கூறினார்:

"குறும்புக்காரப் பெண்ணே, அழுக்குப் பெண்ணே, நீ என்ன செய்து கொண்டிருந்தாய்?"

'மாலாஷா வேண்டுமென்றே அப்படிச் செய்தாள்' என்றாள் அந்தப் பெண்.

இதைக் கேட்ட அகோலியாவின் தாய் மலாஷாவைப் பிடித்து அவள் கழுத்தின் பின்புறத்தில் அடித்தார். ம, அதனால் தெரு முழுவதும் கேட்கும்படி அவள் ஊளையிடத் தொடங்கினாள். அம்மா வெளியே வந்தாள்.

'என் பெண்ணை எதற்காக அடிக்கிறாய்?' என்றாள்; பக்கத்து வீட்டுக்காரனைத் திட்ட ஆரம்பித்தாள். ஒரு வார்த்தை இன்னொன்றுக்கு வழிவகுத்தது, அவர்களுக்குள் கோபமான சண்டை ஏற்பட்டது. ஆட்கள் வெளியே வந்தார்கள். தெருவில் ஒரு கூட்டம் கூடியது. எல்லோரும் கூச்சலிட்டார்கள். யாரும் கவனிக்கவில்லை. அவர்கள் எல்லோரும் சண்டையிட்டுக் கொண்டே இருந்தார்கள். ஒருவர் மற்றொருவரைத் தள்ளிவிடும்வரை சண்டை போட்டார்கள். அந்த விவகாரம் கிட்டத்தட்ட முடிவுக்கு வந்தது. அப்போது அகோலியாவின் வயதான பாட்டி அவர்களிடையே நுழைந்து அவர்களை அமைதிப்படுத்த முயன்றாள். "என்ன நினைக்கிறீர்கள் நண்பர்களே? அப்படி நடந்து கொள்வது சரியா? அதுவும் இப்படி ஒரு நாளில்! இது களிகூருவதற்கான காலமேயன்றி இது போன்ற முட்டாள்தனங்களுக்கான காலமல்ல.'

அவர்கள் மூதாட்டியின் பேச்சைக் கேட்கவில்லை, கிட்டத்தட்ட அவளது கால்களைத் தட்டி விட்டனர். அக்கோல்யாவும் மலாஷாவும் இல்லையென்றால் அவளால் கூட்டத்தை அமைதிப்படுத்த முடிந்திருக்காது. பெண்கள் ஒருவரையொருவர் திட்டிக் கொண்டிருந்தபோது, அகோல்யா தனது மேலங்கியில் இருந்த சேற்றைத் துடைத்துவிட்டு, மீண்டும் குட்டைக்கு சென்றாள். அவள் ஒரு கல்லை எடுத்து குட்டைக்கு முன்னால் இருந்த மண்ணைச் சுரண்டத் தொடங்கினாள். அதன் வழியாகத் தெருவுக்குள் தண்ணீர் ஒழுகுவதற்கு ஒரு வாய்க்கால் அமைத்தாள். உடனே மலாஷாவும் அவளுடன் சேர்ந்துகொண்டு, ஒரு மரத்துண்டைக் கொண்டு வாய்க்காலைத் தோண்ட உதவினாள். ஆண்கள் சண்டையிடத் தொடங்கிய நேரத்தில், சிறுமிகளின் கால்வாயிலிருந்து தண்ணீர் தெருவில் பாய்ந்து ஆண்களை சமாதானப்படுத்த முயன்ற அதே இடத்தை நோக்கி ஓடியது. பெண்கள் அதைப் பின்தொடர்ந்தனர்; ஒன்று அந்தச் சிறு ஓடையின் இருபுறமும் ஓடுகிறது.

"பிடி, மாலாஷா! பிடி!" என்று கத்தினான் அகோயல்யா;

"

; அதேசமயம் மலாஷாவால் சிரிப்பதற்காக பேச முடியவில்லை. மிகவும் மகிழ்ச்சியடைந்த அந்தச் சிறுமிகள் அந்தச் சில்லு தங்கள் ஓடையில் மிதப்பதைப் பார்த்துக் கொண்டிருந்தார்கள் நேராக ஆண்கள் கூட்டத்துக்குள் ஓடினார்கள் அவர்களைக் கண்ட அந்த மூதாட்டி அவர்களிடம், 'உங்களுக்கு வெட்கமாக இல்லையா? இந்தப் பெண்களுக்காகச் சண்டையிடப் போவது, அவர்களே எல்லாவற்றையும் மறந்துவிட்டு, சந்தோஷமாக ஒன்றாக விளையாடிக் கொண்டிருக்கும்போது. அன்பார்ந்த சிறிய ஆத்மாக்கள்! அவர்கள்

உங்களைவிட புத்திசாலிகள்!" ஆண்கள் சிறுமிகளைப் பார்த்து வெட்கப்பட்டு, தங்களைத் தாங்களே சிரித்துக்கொண்டு, ஒவ்வொருவரும் தங்கள் வீட்டிற்குத் திரும்பிச் சென்றனர்.

"நீங்கள் திரும்பிப் பிள்ளைகளைப்போல் ஆகாவிட்டால், பரலோகராஜ்யத்தில் பிரவேசிக்கமாட்டீர்கள்." Bible Verse

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A DAY'S WAIT - ERNEST HEMINGWAY- (Story in Original)

He came into the room to shut the windows while we were still in bed and I saw he looked ill. He was shivering, his face was white, and he walked slowly as though it ached to move.

“What’s the matter, Schatz?”

“I’ve got a headache.”

“You better go back to bed.”

“No. I’m all right.”

“You go to bed. I’ll see you when I’m dressed.”

But when I came downstairs he was dressed, sitting by the fire, looking a very sick and miserable boy of nine years. When I put my hand on his forehead I knew he had a fever.

“You go up to bed,” I said, “you’re sick.”

“I’m all right,” he said.

When the doctor came he took the boy’s temperature.

“What is it?” I asked him.

“One hundred and two.”

Downstairs, the doctor left three different medicines in different colored capsules with instructions for giving them. One was to bring down the fever, another a purgative, the third to overcome an acid condition. The germs of influenza can only exist in an acid condition, he explained. He seemed to know all about influenza and said there was nothing to worry about if the fever did not go above one hundred and four degrees. This was a light epidemic of flu and there was no danger if you avoided pneumonia.

Back in the room I wrote the boy’s temperature down and made a note of the time to give the various capsules.

“Do you want me to read to you?”

“All right. If you want to,” said the boy. His face was very white and there were dark areas under his eyes. He lay still in the bed and seemed very detached from what was going on.

I read aloud from Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates; but I could see he was not following what I was reading.

“How do you feel, Schatz?” I asked him.

“Just the same, so far,” he said.

I sat at the foot of the bed and read to myself while I waited for it to be time to give another capsule. It would have been natural for him to go to sleep, but when I looked up he was looking at the foot of the bed, looking very strangely.

“Why don’t you try to go to sleep? I’ll wake you up for the medicine.”

“I’d rather stay awake.”

After a while he said to me, “You don’t have to stay in here with me, Papa, if it bothers you.”

“It doesn’t bother me.”

“No, I mean you don’t have to stay if it’s going to bother you.”

I thought perhaps he was a little lightheaded and after giving him the prescribed capsules at eleven o’clock I went out for a while.

It was a bright, cold day, the ground covered with a sleet that had frozen so that it seemed as if all the bare trees, the bushes, the cut brush and all the grass and the bare ground had been varnished with ice. I took the young Irish setter for a little walk up the road and along a frozen creek, but it was difficult to stand or walk on the glassy surface and the red dog slipped and slithered and I fell twice, hard, once dropping my gun and having it slide away over the ice.

We flushed a covey of quail under a high clay bank with overhanging brush and I killed two as they went out of sight over the top of the bank. Some of the covey lit in trees, but most of them scattered into brush piles and it was necessary to jump on the ice-coated mounds of brush several times before they would flush. Coming out while you were poised unsteadily on the icy, springy brush they made difficult shooting and I killed two, missed five, and started back pleased to have found a covey close to the house and happy there were so many left to find on another day.

At the house they said the boy had refused to let any one come into the room.

“You can’t come in,” he said. “You mustn’t get what I have.”

I went up to him and found him in exactly the position I had left him, white-faced, but with the tops of his cheeks flushed by the fever, staring still, as he had stared, at the foot of the bed.

I took his temperature.

“What is it?”

“Something like a hundred,” I said. It was one hundred and two and four tenths.

“It was a hundred and two,” he said.

“Who said so?”

“The doctor.”

“Your temperature is all right,” I said. “It’s nothing to worry about.”

“I don’t worry,” he said, “but I can’t keep from thinking.”

“Don’t think,” I said. “Just take it easy.”

“I’m taking it easy,” he said and looked straight ahead. He was evidently holding tight onto himself about something.

“Take this with water.”

“Do you think it will do any good?”

“Of course it will.”

I sat down and opened the Pirate book and commenced to read, but I could see he was not following, so I stopped.

“About what time do you think I’m going to die?” he asked.

“What?”

“About how long will it be before I die?”

“You aren’t going to die. What’s the matter with you?”

“Oh, yes, I am. I heard him say a hundred and two.”

“People don’t die with a fever of one hundred and two. That’s a silly way to talk.”

“I know they do. At school in France the boys told me you can’t live with forty-four degrees. I’ve got a hundred and two.”

He had been waiting to die all day, ever since nine o’clock in the morning.

“You poor Schatz,” I said. “Poor old Schatz. It’s like miles and kilometers. You aren’t going to die. That’s a different thermometer. On that thermometer thirty-seven is normal. On this kind it’s ninety-eight.”

“Are you sure?”

“Absolutely,” I said. “It’s like miles and kilometers. You know, like how many kilometers we make when we do seventy miles in the car?”

“Oh,” he said.

But his gaze at the foot of the bed relaxed slowly. The hold over himself relaxed too, finally, and the next day it was very slack and he cried very easily at little things that were of no importance.

A DAY'S WAIT - ERNEST HEMINGWAY---(summary)

A Day’s Wait’ is one of Ernest Hemingway’s shortest short stories, running to just a few pages. It was published in 1927 in his collection The Snows of Kilimanjaro and Other Stories. In just a few pages, ‘A Day’s Wait’ covers a number of key features of Hemingway’s work as a whole, and so despite not being one of his best-known stories, it’s oddly representative of his oeuvre as a whole.

‘A Day’s Wait’: plot summary

The story is narrated by an unnamed father of a nine-year-old boy named Schatz. The boy falls ill with influenza. He tells his father he has a headache and when his father feels the boy’s forehead, it’s clear he has a fever.

The doctor comes to examine the boy and tells him that his temperature is 102 degrees. However, the boy mistakenly thinks the doctor means 102 degrees Celsius rather than 102 Fahrenheit. Because he believes his temperature is much higher than it is, Schatz becomes convinced he is going to die from the illness, as he had been told in school that any temperature over 44 degrees would mean certain death.

The story’s title, ‘A Day’s Wait’, refers to the boy’s day spent waiting to die, as he believes he will. However, the father, who narrates the story, doesn’t realise that boy believes he is approaching imminent death, and simply ascribes his son’s strange behaviour (such as staring straight ahead) to the illness.

The father tries to read from Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates to keep his son entertained in his sickbed, but Schatz doesn’t seem to be listening. Then the father goes out with his dog for a walk, and shoots quail.

When the boy’s father returns and talks to his son, he realises his son’s mistake and explains it to him – using the analogy of confusing kilometres with miles to explain the difference between Celsius and Fahrenheit temperatures – and the son feels relieved and begins his recovery.

--------------------------------------

A DAY'S WAIT STORY BY ERNEST HEMINGWAY :

ஷாட்ஸ் என்ற ஒன்பது வயது சிறுவனின் பெயரிடப்படாத தந்தையால் கதை விவரிக்கப்படுகிறது. சிறுவனுக்கு இன்ஃப்ளூயன்ஸா காய்ச்சல் ஏற்படுகிறது. அவன் தனது தந்தையிடம் தனக்கு தலைவலி இருப்பதாக கூறுகிறர், அவரது தந்தை சிறுவனின் நெற்றியை உணர்ந்தபோது, அவருக்கு காய்ச்சல் இருப்பது தெளிவாகிறது.

மருத்துவர் வந்து சிறுவனைப் பரிசோதித்து, அவனது வெப்பநிலை 102 டிகிரி என்று கூறுகிறார். ஆனால், டாக்டர் என்றால் 102 பாரன்ஹீட் என்பதற்கு பதிலாக 102 டிகிரி செல்சியஸ் என்று சிறுவன் தவறாக நினைக்கிறான். தனது வெப்பநிலை இப்போது இருப்பதை விட மிக அதிகமாக இருப்பதாக அவர் நம்புவதால், 44 டிகிரிக்கு மேல் வெப்பநிலை இருந்தால் நிச்சயமான மரணத்தை அர்த்தப்படுத்தும் என்று பள்ளியில் அவரிடம் கூறப்பட்டதால், ஷாட்ஸ் நோயால் இறக்கப் போகிறார் என்று உறுதியாக நம்புகிறார்.

கதையின் தலைப்பு, 'ஒரு நாள் காத்திருப்பு', சிறுவனின் நாள் இறப்பதற்காக காத்திருப்பதைக் குறிக்கிறது, அவர் நம்புகிறார். இருப்பினும், கதையை விவரிக்கும் தந்தை, சிறுவன் உடனடி மரணத்தை நெருங்குவதாக நம்புகிறான் என்பதை உணரவில்லை, மேலும் தனது மகனின் விசித்திரமான நடத்தையை (நேராக முன்னால் பார்ப்பது போன்றவை) நோயைக் காரணம் காட்டுகிறார்.

தந்தை தனது மகனை நோய்வாய்ப்பட்ட படுக்கையில் மகிழ்விக்க ஹோவர்ட் பைலின் பைரேட்ஸ் புத்தகத்திலிருந்து படிக்க முயற்சிக்கிறார், ஆனால் ஷாட்ஸ் அதைக் கேட்பதாகத் தெரியவில்லை. பின்னர் தந்தை தனது நாயுடன் நடைப்பயிற்சிக்கு வெளியே செல்கிறார், மற்றும் காடை சுடுகிறார்.

சிறுவனின் தந்தை திரும்பி வந்து தனது மகனிடம் பேசும்போது, அவர் தனது மகனின் தவறை உணர்ந்து அதை அவனுக்கு விளக்குகிறார் - செல்சியஸ் மற்றும் பாரன்ஹீட் வெப்பநிலைக்கு இடையிலான வேறுபாட்டை விளக்க மைல்களுடன் கிலோமீட்டர்களை குழப்பும் ஒப்புமையைப் பயன்படுத்துகிறார் - மகன் நிம்மதியடைந்து தனது மீட்பைத் தொடங்குகிறார்.

------------------------------The Story - ( IN ORIGINAL )

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1ST AND LAST PARAS IN “Two old Men” by Leo Tolstoy

There were once two old men who decided to go on a pilgrimage to worship God at Jerusalem. One of them was a well-to-do peasant named Efím Tarásitch Shevélef. The other, Elisha Bódrof, was not so well off.

Efím sighed, and did not speak to Elisha of the people in the hut, nor of how he had seen him in Jerusalem. But he now understood that the best way to keep one's vows to God and to do His will, is for each man while he lives to show love and do good to others.

________________________________________________________________________________

THE MERCHANT OF VENICE

A word of caution : Learners of English are to avoid the interference of the vernacular. Yet Tamil translation is given only for the sake of UG students who do not have English as Major/Main Branch.

ஒரு எச்சரிக்கை குறிப்பு : ஆங்கிலம் கற்பவர்கள் வட்டார மொழியின் குறுக்கீட்டைத் தவிர்க்க வேண்டும். ஆனாலும் ஆங்கிலம் முதன்மைப் பிரிவாக இல்லாத இளங்கலை மாணவர்களுக்காக மட்டுமே தமிழ் மொழிபெயர்ப்பு வழங்கப்படுகிறது.

கதைச்சுருக்கம்

ஒரு உன்னதமான ஆனால் பணமில்லாத Venice நகரத்து பசானியோ, தனது பணக்கார வணிக நண்பர் அன்டோனியோவிடம் கடன் கேட்கிறான், இப்பணத்தின் மூலம் உயர்குலப் பெண்ணான போர்ஷியாவை கவர்ந்திழுக்க பசானியோ ஒரு பயணத்தை மேற்கொள்ள முடியும். அண்டோனியோவின் பணம் வெளிநாட்டு முயற்சிகளில் முதலீடு செய்யப்பட்டுள்ளதால், ஷைலாக் என்ற யூத வட்டிக்கடைக்காரரிடமிருந்து அந்தத் தொகையை கடன் வாங்குகிறார், கடனை சரியான நேரத்தில் திருப்பிச் செலுத்த முடியாவிட்டால், அன்டோனியோ ஒரு பவுண்டு சதையை இழக்க நேரிடும் என்ற நிபந்தனையின் பேரில் கடன் வாங்குகிறார் . அன்டோனியோ ஷைலாக்குடன் பண பரிவர்த்தனை செய்ய தயங்குகிறார், அன்டோனியோவைப் போலல்லாமல், ஷைலாக் வட்டிக்கு கடன் கொடுப்பதற்காக பசானியோ வெறுக்கிறார் .பசானியோ வட்டி எதுவும் இல்லாமல் பசானியோவுக்கு பணத்தை வழங்குகிறார் வட்டிக்கு கடன் கொடுப்பது கிறிஸ்தவத்தின் உணர்வையே மீறுவதாக அண்டோனியோ கருதுகிறார். ஆயினும்கூட, பசானியோவுக்கு உதவ அவருக்கு உதவி தேவைப்படுகிறது. இதற்கிடையில், பசானியோ போர்ஷியாவின் தந்தையின் உயிலின் நிபந்தனைகளை பூர்த்தி செய்கிறார், மூன்று பெட்டிகளில் இருந்து அவளுடைய உருவப்படம் உள்ள ஒன்றை தேர்ந்தெடுத்தார், மேலும் அவரும் போர்ஷியாவும் திருமணம் செய்து கொண்டனர்

அன்டோனியோவின் கப்பல்கள் கடலில் காணாமல் போய்விட்டன என்ற செய்தி வருகிறது. தனது கடனை சேகரிக்க முடியாமல், ஷைலாக் அன்டோனியோவை ஒரு பயங்கரமான, கொலைகார பழிவாங்கலை செயல்படுத்த நீதியைப் பயன்படுத்த முயற்சிக்கிறார்: அவர் தனது பவுண்டு சதையைக் கோருகிறார். ஷைலாக்கின் பழிவாங்கும் விருப்பத்தின் ஒரு பகுதி, நாடகத்தின் கிறிஸ்தவர்கள் ஒன்றிணைந்து அவரது மகள் ஜெசிகாவை அவரது வீட்டிலிருந்து ஓடிப்போகச் செய்து, கிறிஸ்டியன் லோரென்சோவின் மணமகளாக மாறுவதற்காக அவரது செல்வத்தின் கணிசமான பகுதியை அவளுடன் எடுத்துச் செல்ல உதவுகிறார்கள். ஷைலாக்கின் பழிவாங்கும் திட்டம் ஒரு வழக்கறிஞராக மாறுவேடத்தில் இருக்கும் போர்ஷியாவால் முறியடிக்கப்படுகிறது, ஷைலாக் ஒரு சட்ட சிக்கலால் ஷைலாக்கை நோக்கி அட்டவணையை மாற்றுகிறார்: அவர் சதையை மட்டுமே எடுக்க வேண்டும், மேலும் ஏதேனும் இரத்தம் சிந்தப்பட்டால் ஷைலாக் இறக்க வேண்டும். இதனால், ஒப்பந்தம் ரத்து செய்யப்படுகிறது, மேலும் ஷைலாக் தனது சொத்தில் பாதியை அன்டோனியோவுக்கு கொடுக்க உத்தரவிடப்படுகிறார், ஷைலாக் கிறிஸ்தவ மதத்திற்கு மாறினால் பணத்தை எடுக்க மாட்டேன் என்று ஒப்புக்கொள்கிறார், மேலும் அவரது வாரிசு மறுக்கப்பட்ட மகளை தனது விருப்பத்திற்கு மீட்டெடுக்கிறார். ஷைலாக் ஒப்புக்கொள்வதைத் தவிர வேறு வழியில்லை.. உண்மையில், அன்டோனியோவின் சில கப்பல்கள் பாதுகாப்பாக வந்து சேர்ந்தன என்ற செய்தியுடன் நாடகம் முடிகிறது.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Protoganist:

A protagonist is a central character who pushes a story forward. The protagonist is also the principal character in a literary work, such as a drama or story

PROTOGANIST :ஒரு கதையை முன்னோக்கி நகர்த்தும் மைய கதாபாத்திரம்

கதாநாயகன் என்பவன் ஒரு கதையை முன்னோக்கி நகர்த்தும் மையக் கதாபாத்திரம். நாடகம் அல்லது கதை போன்ற இலக்கியப் படைப்புகளில் கதாநாயகன் முதன்மைப் பாத்திரம்.

ANTAGONIST :

antagonist

: one that contends with or opposes another : adversary, opponent

political antagonists

எதிரி

: மற்றொன்றுடன் போட்டியிடும் அல்லது எதிர்க்கும் ஒன்று : எதிரி, எதிரி

அரசியல் எதிரிகள்

In Shakespeare’s Drama THE MERCHANT OF VENICE, SHYLOCK is the antagonist.

In Bernard Shah’s Drama, Pygmalion, Eliza Doolittle is the protagonist (the main character)

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ROMEO AND JULIET - SUMMARY

கதைச்சுருக்கம்

இரண்டு சக்திவாய்ந்த குடும்பங்களுக்கு இடையிலான பழமையான பகைமை இரத்தக்களரியாக வெடிக்கிறது. முகமூடி அணிந்த மாண்டேகுக்களின் ஒரு குழு ஒரு கபுலெட் விருந்தை நுழைவாயிலில் உடைப்பதன் மூலம் மேலும் மோதலை எதிர்கொள்கிறது. ஒரு இளம் காதல் நோயுற்ற ரோமியோ மாண்டேகு உடனடியாக ஜூலியட் கபுலெட்டை காதலிக்கிறாள், அவள் தனது தந்தையின் விருப்பமான கவுண்டி பாரிஸை திருமணம் செய்யவிருக்கிறாள். ஜூலியட்டின் செவிலியரின் உதவியுடன், பெண்கள் அடுத்த நாள் தம்பதியரை திருமணம் செய்து கொள்ள ஏற்பாடு செய்கிறார்கள், ஆனால் ஒரு தெருச் சண்டையை நிறுத்த ரோமியோவின் முயற்சி ஜூலியட்டின் சொந்த உறவினரான டைபால்ட்டின் மரணத்திற்கு வழிவகுக்கிறது, அதற்காக ரோமியோ நாடு கடத்தப்படுகிறார். ரோமியோவுடன் மீண்டும் இணைவதற்கான ஒரு அவநம்பிக்கையான முயற்சியில், ஜூலியட் துறவியின் சதியைப் பின்பற்றி, தனது சொந்த மரணத்தை போலியாக நடிக்கிறாள். செய்தி ரோமியோவை சென்றடையவில்லை, ஜூலியட் இறந்துவிட்டதாக நம்பி, அவளது கல்லறையில் தனது உயிரை மாய்த்துக் கொள்கிறான். ஜூலியட் கண்விழித்து ரோமியோவின் சடலம் தனக்கு அருகில் இருப்பதைக் கண்டு தற்கொலை செய்து கொள்கிறாள். துக்கமடைந்த குடும்பம் தங்கள் பகையை முடிவுக்குக் கொண்டுவர ஒப்புக்கொள்கிறது.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

THE WINTEWR'S TALE - SUMMARY

கதைச்சுருக்கம்

பொஹிமியாவின் மன்னரான பொலிக்சீன்ஸ், தனது குழந்தை பருவ நண்பரான சிசிலியாவின் மன்னர் லியோன்டெஸ் மற்றும் அவரது மனைவி ராணி ஹெர்மியோன் ஆகியோரின் அரசவைக்கு ஒன்பது மாத பயணமாக வந்துள்ளார்.

நிறைமாத கர்ப்பிணியான தனது மனைவி பொலிக்சீன்ஸுடன் உறவு வைத்திருப்பதாக லியோன்டெஸ் (தவறாக) நம்புகிறார். லியோன்டெஸ் தனது மிகவும் நம்பகமான அரசவையாளரான கமிலோவை பொலிக்சீன்ஸுக்கு விஷம் கொடுக்க வற்புறுத்த முயற்சிக்கிறார்.

ராணி நிரபராதி என்று நம்பும் காமிலோ பொலிக்சீன்ஸை எச்சரிக்கிறார், அவர்கள் ஒன்றாக போஹேமியாவுக்கு புறப்படுகிறார்கள்.

தொலைந்து போன குழந்தைகள்:

ஹெர்மியோனியின் புதிதாகப் பிறந்த மகளை ஒரு பாலைவனக் கரையில் விட்டுச் செல்ல மற்றொரு அரசவை உறுப்பினரான ஆன்டிகோனஸ் உத்தரவிடப்படுகிறார்.

லியோன்டெஸ் ஹெர்மியோனை தேசத்துரோகத்திற்காக விசாரிக்கிறார்; அப்பல்லோ தான் நிரபராதி என்று கூறிய உண்மையை அவர் மறுக்க, அவரது மகன் மாமிலியஸ் இறந்து போகிறார். அப்போது ராணியும் இறந்துவிட்டதாக அவனிடம் கூறப்படுகிறது.

ஆன்டிகோனஸ் பெண் குழந்தையை பொஹிமியா கடற்கரையில் விட்டுச் செல்கிறார், அங்கு அவர் ஒரு கரடியால் துண்டு துண்டாக கிழிக்கப்படுகிறார். ஒரு வயதான மேய்ப்பனும் அவனது கோமாளி மகனும் குழந்தையைக் கண்டுபிடித்து, தங்கள் குடும்ப உறுப்பினராக வளர்த்து, அதற்கு பெர்டிடா என்று பெயரிடுகிறார்கள்.

16 ஆண்டுக ளுக்குப் பிறகு

ஆடு மேய்க்கும் மேய்ப்பராக மாறுவேடமிட்டு வரும் பொலிக்சீனின் மகன் இளவரசர் ஃப்ளோரிஸெல் பெர்டிடாவை காதலிக்கிறார்.

முரட்டு வியாபாரி ஆட்டோலிகஸ் மேய்ப்பர்களிடம் பணம் பறிக்கிறான். பொலிக்சீன்ஸும் காமிலோவும் மாறுவேடத்தில் கிராமப்புறங்களுக்கு வருகிறார்கள்; தாழ்ந்த குலத்தில் பிறந்த ஒரு மேய்ப்பனைக் காதலித்ததற்காக தனது மகனை மன்னர் கண்டிக்கும்போது, ஃப்ளோரிஸலும் பெர்டிடாவும் காமிலோவின் உதவியுடன் சிசிலியாவுக்கு தப்பி ஓடுகிறார்கள்.

மேய்ப்பனும் கோமாளியும் பின்தொடர்கிறார்கள், பெர்டிட்டாவின் உண்மையான அடையாளத்தை வெளிப்படுத்தும் டோக்கன்களைக் கொண்டு வருகிறார்கள். ஹெர்மியோனிக்கு மிகவும் விசுவாசமான பெண்மணியான பவுலினா, இறந்த ராணியின் சிலையை வெளிப்படுத்தி, ஒரு பெரிய அதிசயத்திற்கு தங்களை தயார்படுத்திக் கொள்ளுமாறு அனைவரிடமும் கூறுகிறார்.

சிலை எவ்வளவு அழகாகவும் தத்ரூபமாகவும் இருக்கிறது என்று அவர்கள் கருத்து தெரிவிக்கிறார்கள், அது உயிர் பெறுகிறது. ஹெர்மியோனும் லியோன்டெஸும் மீண்டும் இணைகிறார்கள், ஏனெனில் அவர்களின் மகள் பெர்டிட்டா ஃப்ளோரிஸலுக்கு நிச்சயிக்கப்பட்டிருக்கிறாள்

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The short story ‘Lalajee’ opens with the arrival of a passenger train from Samaria Ghat to a location known as ‘Mokemeh Ghat’. It is told in the first person. The narrator observes a man exiting a broad-gauge passenger train. The appearance of that man is described in depth. He is quite frail, with eyes that have sunk far into their sockets. He only wears patched clothing; it was formerly white. He is carrying a tiny parcel that is tied with a bright handkerchief. His walking manner demonstrates that he is terribly sick.

The sick man makes his way towards the Ganges bank with his frail steps. He lowers himself to wash his face. He then spreads the sheet along the Ganges riverbank. The narrator recognises that this sick man is adamant about not continuing his journey on the same train. He opens his eyes and notices the storyteller standing nearby.

The narrator is informed by the sick man that he does not wish to travel by train due to his terminal illness. He comes to spend his final moments near the sacred Ganges. He is conscious of his physical limitations. The narrator, too, is aware that cholera is an epidemic in many locations during this summer season and that the sick man may have been infected. From his terribly sick state, he affirms that he is solely suffering from Cholera. The narrator learns from the sick man that he has no friends in this location. As a result, this narrator is gracious enough to transport him to his home, which is located two hundred yards from the Ganges.

Prior to the invention of electric fans, people used Punkahs in their homes, which were propelled forward by pulling a cord through a pulley. The coolie must continuously pull the string in order to circulate the air in the room. He has a large number of punkah coolies working in his home. He has provided them with separate houses in order to keep them close to his residence. The house of the punkah’ coolie is currently vacant. As a result, he transports this sick man to this dwelling. This residence is distinct from the servants’ quarters. The servants prefer not to reside near a Cholera patient. Due to the epidemic’s nature, they may also become fatalists. As a result, he is forced to remain at the punkah coolie’s house, which is located a considerable distance from the servants’ quarters.

The storyteller had spent eleven years at Mokameh Ghat. He has employed a sizable labour force. They resided in close proximity to him or in surrounding communities. The narrator has observed numerous Cholera patients throughout his ten-year stay. Seeing their pitiful state, the narrator wishes that if he ever contracts his terrible ailment, a Good Samaritan, or a good man, would take pity on him and shoot him in the head or give him an overdose of opium. He would rather die than suffer from Cholera.

The narrator provides statistics on the number of individuals who die each year from cholera. In India, people die of Cholera primarily due to dread of disease, not the disease itself. Visitors to India have a strong belief in fate. They think that a man cannot die before reaching his predetermined age. It is plainly implied that people die primarily as a result of their fear of disease, not from the disease itself.

The sick man is suffering from cholera, which has taken a severe toll on him. The narrator is convinced that his faith and treatment will be sufficient to ensure his survival. He is accompanied by three additional cholera cases. He convinces the sick man that he will be healed of his illness. He instils confidence in the sick man’s psyche. This sick man regained his health and strength as a result of his treatment and inspired confidence. The completely restored man relates his story only at the conclusion of the week.